At this time our group is rolling off of the back of James Seitz and toward Peter J. Rabinowitz. Seitz, in “A Rhetoric of Reading” helps us identify what a capable reader is, but that in itself is a layered experience. An experience that starts with readers attempting to answer the question, What type of reader do you need to be to read a particular text?

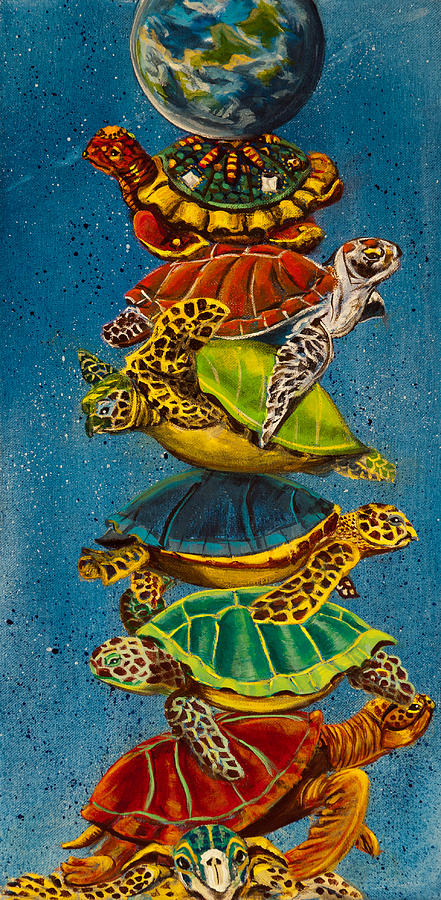

This question fascinates me every time I encounter it. Let’s look at this question in terms of John Green’s Turtles All the Way Down. What type of person do I have to be to read this novel? Well, there’s a list of things.

I would have to be someone who believes that Aza is an accurate representation of a teenage girl with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I would have to believe that her OCD can have this much power over her. I have to believe the internal struggle could lead someone to drink sanitizer in order to feel “clean”. I have to be open to the possible effects of Aza’s OCD compulsions and rituals. And looking past her mental health, a reader has to understand the feelings around an identity crisis, whether it be from experience or understanding the possibility of having one. Someone who does, or at some point, view themselves as being authored by someone else, as a sidekick, as fictional. And hopefully, someone who can also see themselves as a singular proper noun, like Aza, by the time they finish reading.

By identifying with these parts of the narrative, we are able to begin to enter into the role of the “capable reader.” Seitz defines this role as a reader “who not only has the ability to ‘follow’ the text but also the ability to jump ahead of it” (146). We are now stepping into the first part of this role, if we can sit in the chair that Turtles All the Way Down offers, we can enter the world of the novel.

But there are things we need to be careful of. The goal is to get to the second part of the definition, the ability to jump ahead of the text and infer how the conflict might unfold. However, readers often run into a problem where they can’t enter the world of the text. They can’t submit to it (though they can at least imagine someone who could). Instead, they end up becoming what Kopp calls “inauthentic resistant reader” where one never lets themselves enter the world of the text. The sort of person who says no just to say no.

An inauthentic resistant reader for this text would be someone that sees Aza as a monster. They would be the type of reader that believes Aza to be exaggerating her struggle with OCD. As she drinks the sanitizer, she becomes this “crazy” person who should be locked up and is out of control, etc, etc. It is the capable reader (the authorial reader/narrative reader) that rejects any of these ideas. They understand the power of compulsions and irrational thoughts that come with this disorder.

So we have the inauthentic resistant reader, who we are trying not to be, and the capable reader that is our goal. But how do we gain the ability to predict the text? And how do we not submit too far into the text? What dangers await us if we submit too much? We can begin to answer these questions by looking at Peter J. Rabinowitz in “Truth in Fiction”.

If we can enter what Rabinowitz calls the authorial audience we can start to make predictions. This audience is created as the author, “[makes] certain assumptions about his reader’s beliefs, knowledge, and familiarity with conventions” (126). This audience has to have a certain bank of knowledge in order to ‘get’ the text. So as a member of this audience we can believe that Aza could be a real person with this version of OCD that affects her the way it does. She is also a person that could feel fictional or coded as a Sidekick and struggle to create her own sense of self. Now we’ve submitted to the possibility of the text and we can make predictions based on these assumptions. This is the power of the authorial audience. They can submit to the world of the text but have the power to question it.

The danger comes if we continue to submit and end up in the ideal narrative audience. This audience, Rabinowitz refers to as “[an audience that] believes the narrator, accepts his judgments, sympathizes with his plight, laughs at his jokes even when they are bad” (134). The ideal narrative audience has completely submitted to the text. Aza’s personification of her OCD is real. The “demon” becomes a real flesh and blood character that threatens Aza. They have no power or agency over the narrative.

There is a moment where the reader can make a choice. A choice to either continue in the ideal narrative audience or enter into the authorial audience. Aza has just woken up in the hospital, this time after the sanitizer incident,

“The next morning, you wake up in a hospital bed, staring up at ceiling tiles. Gingerly, carefully, you assess your own consciousness for a moment. You wonder, Is it over?” 147

Here, the point of view has changed. The entire novel so far has been written in the first person, the reader has access to Aza’s thoughts, feelings, emotions, and biases. So now who is ‘you’ and who is this you talking to?

In this short chapter, and the only instance where this change happens in the novel, the you is the “demon” that Aza uses to personify her OCD. She has submitted to the ideal narrative audience and no longer has the power to question the irrational thoughts of the demon. The demon is in control and addressing Aza within her own body. Then, in the next chapter, the point of view has changed back to Aza with her newfound motivation to work through her mental illness.

Fast forward to the end of the novel, Aza is lying with Davis looking at the stars holding hands and she thinks, “your hand—no, my hand—no, our hand—in his” (181). We see another moment where Aza almost gives control back to the demon. Instead of surrendering, she accepts it as a part of her. The ‘you’ versus ‘I’ becomes ‘our’. Now, this demon has lost all of its power. Aza finally has the agency she’s been searching for. The audiences begin to shift, the narrative audience is, hopefully, developing with Aza.

And it continues as she is finally able to see herself as a “self,” an “I, a singular proper noun, and I that would go on, if always in a conditional tense” (181). Aza has finally broken from the ideal narrative audience. Had she, or the reader, allowed the demon to hold control over them, they would still be lost within the world of the ideal narrative audience. There would be no escape and they would still be searching and struggling through the irrational thoughts and behaviors that the demon calls for.

The reader has watched Aza move between the audiences. She is able to end her story in the authorial audience. Now she finally has the agency to question her mental health and adapt it into her own sense of self. She is no longer controlled by it. And hopefully, the reader has made this change with Aza, instead of spiraling within the irrational thoughts of her ‘OCD demon’.

I agree with the types of readers, as I can see myself in two of them. To start, I was a capable reader, for I followed along with the narrative, and I jumped ahead as I was excited to read about the romance between Aza and Davis and her friendship with Daisy. I thought Daisy was mean for she put Aza down, even when she knew that Aza had a mental illness, but she talked down to her. I understand that Aza should have asked Daisy about her life, yet, there was a better way to talk about it. However, I believe I went from a capable reader to an inauthentic reader as I was starting to notice Aza’s OCD was getting the best of her as she drank hand sanitizer to keep herself ‘pure’. Therefore, I saw her as becoming the monster she thought was inside her, but it was her. I do not know if you could be two types of readers, but I believe you can, as someone can start as a capable reader and your stay has one or change to another reader.

LikeLike

I do see myself as a capable reader, I was assuming all of Aza’s problems were caused by her OCD even though there’s more than just that. But at the same time I can see myself as an inauthentic resistant reader, because I do feel that there are moments when I’m reading about Aza’s life and just wanting to shake her because what she has is being blown out of proportion. For example drinking hand sanitizer is a little over the top and even more harmful than her OCD. Like Paige I’m not sure if it’s possible to be both but I can see it both ways. Now when you bring up her waking up in the hospital, it was something I didn’t even realize, how it went from first person to it being me, and in my mind I was just so used to her talking about herself and being trapped in her head that I never realized the change.

LikeLike

Hello Angelina, you bring up interesting points about the different types of readers, but I think they could have been expanded upon. I think there could be even more perspectives coming from the inauthentic resistant reader. One example could be that they don’t believe that Aza is an accurate depiction of someone who struggles with OCD. After all, one person with a specific mental illness like OCD can have a completely different experience from another person who also has OCD. It could be as simple as someone thinking “that’s not what it’s like” when they see Aza and looking at her struggle with OCD. I think this has a lot to do with the fact that the book focuses so much on her mental illness and doesn’t highlight some of her other inner struggles. I am not a psychologist, but she is displaying many character traits of someone who struggles with Germaphobia. Something like a simple fear of hers might not seem that important at first, but if it were highlighted more in the narrative, maybe this inauthentic resistant reader could begin to understand what she is going through. They might not insert themselves in the world but it’s a start.

LikeLike